The New Israeli Government: Challenges Ahead and Key Stakeholders

July 21, 2021

APCO alumna Hannah Katz contributed to this analysis.

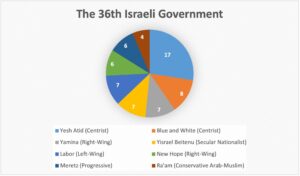

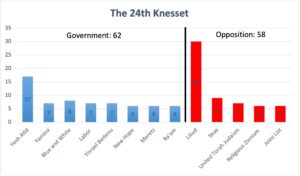

On June 13, 2021, Israel’s 36th government was approved, composed of eight parties broadly representing the political left, center and right-wing camps. The parties in total hold a narrow 62-seat majority in the 120-seat Israeli parliament, Knesset, and greatly differ on policy and ideology. It should be emphasized one of the Members of Knesset, Yamina’s Amichai Chikli, is not wholly committed to the new government, in effect giving the government a razor-thin 61-seat majority. They have been united by a shared interest in replacing Benjamin Netanyahu, who had served as prime minister since 2009 and is standing trial on charges of three criminal offenses. Netanyahu has furthermore been accused by critics of fostering societal tensions and governing through divisiveness. The new government was approved by a slim 60-59 vote, highlighting its narrow mandate and the challenges it will face in upholding internal unity as it seeks to advance its policy agenda.

The new government features a rotating premiership agreement: right-wing nationalist Yamina party leader Naftali Bennett is serving as prime minister until August 2023, after which centrist Yesh Atid party leader Yair Lapid will serve the second half of the four-year term, until November 2025. Lapid will serve the first two years serve as Minister of Foreign Affairs. The government was established by Lapid, who had been tasked with a mandate to try and form a government by outgoing President Reuven Rivlin because incumbent Prime Minister Netanyahu had been unsuccessful in his mandate to assemble a coalition. Despite being the largest party in the March 2021 election with 30 seats, Netanyahu’s Likud was unable to assemble a coalition after being tasked with a 28-day mandate.

Lapid’s efforts were nearly derailed in mid-May, as the security situation escalated between Israel and the Hamas-governed Gaza Strip and the interim government under Netanyahu launched “Operation Guardian of the Walls.” The fighting contributed to Jewish-Arab violence within Israel, including in several “mixed cities” such as Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Haifa, Lod, Acre, and Jerusalem. Both Bennett’s party and the conservative Arab-Muslim party Ra’am withdrew from coalition talks during the 11-day conflict, as relations between Israel’s Jewish and Arab populations deteriorated to their worst level in decades. The new government that emerged following the internal violence was thus forged by pragmatic compromises from the various sides of the political spectrum, which committed to fostering national unity in the wake of heightened domestic turmoil.

A Coalition of Diversity and Firsts. The new 62-seat government—or, as noted above, arguably 61 seats—is Israel’s most unconventional ever. Never has a coalition been formed with its leading party holding only 17 seats or the prime minister hailing from a party with only seven mandates. Nor has a previous government ever featured such a broad amalgamation of political parties from across the traditional left-right spectrum. The government is also Israel’s most diverse ever, highlighted by the unprecedented participation of an Arab party in the coalition, the conservative Muslim party Ra’am—which itself played a central kingmaker role in the coalition talks—and a record eight Arab MKs. Additionally there are several other milestones worth noting that highlight this government’s highly diverse nature.

Politically Experienced, but Less Experience in Government. Many members of the coalition’s right-wing and centrist parties have sat in previous governments led by Benjamin Netanyahu and are intricately familiar with key national issues and policy questions, including economic matters and the means for advancing government actions to address them. In contrast, while many members of the left-wing parties and Ra’am have longstanding experience serving in the Knesset, they have exclusively sat in the opposition and are less familiar with government policymaking. Other members of the coalition are relative newcomers to politics, such as Minister of Economy and Industry Orna Barbivai (Yesh Atid), who entered Knesset only in 2019 after a 30-year military career. This presents an opportunity for the business community to engage these newcomers, both to leading a government and the political system entirely, building productive relationships with these newly important stakeholders, and exploring avenues for cooperation.

Domestic Focus on Bread-and-Butter Issues, Avoiding Ideological Ones. The government is expected to advance policies on issues for which there is a broad national consensus, such as passing the country’s first budget since 2018, encouraging a post-COVID-19 economic recovery, increasing affordable housing and upgrading the public transportation network and infrastructure systems. In contrast, it is likely the government will avoid addressing issues with widespread disagreements among the coalition’s parties, such as West Bank settlements and reforms to the judicial system. While the coalition features the strong influence of secular parties, it is uncertain if it would prioritize secular interests on religion-state issues, such as military enlistment of ultra-Orthodox men and expanded business activity on the Jewish Sabbath. It would likely seek to avoid tackling these controversial issues head-on as a means to entice religious parties into joining its currently narrow 62-seat coalition and abandoning their alliance with Netanyahu and avoid deepening societal rifts.

Increased Focus on the Arab Community. The new government courted Ra’am to join by agreeing to double state funding to the Arab community, pledging NIS 53 billion (USD 16 billion) over five years. The investment will also include sigcombatting rising crime and violence in Arab towns and accelerating housing construction and land planning and zoning for Arab families. The government also committed to freezing the demolition of homes built without permits in Arab villages and granting official status to Bedouin towns in the Negev Desert. The new government’s commitment to the Arab community will also extend to the digital and tech spaces, through the implementation of measures such as improving high-speed Internet connections in Arab localities, increasing digital literacy and associated STEM-related career development tracks, and creating technology parks in proximity to Arab population centers.

Prior to joining the Lapid-led coalition, Ra’am had been courted to join a government under Netanyahu, while the other Arab party Joint List—from which Ra’am split ahead of the March 2021 election—was courted in the last election cycle. These developments highlight a process of normalizing Arab parties’ participation in the Israeli government, after several decades in which this was considered taboo by both the Arab public and the Israeli Zionist leadership. Moving forward, Arab parties can be expected to take part in future Israeli governments and overall play greater roles in national decision-making.

More Committed to Multilateralism and Progressivism. The new government features many influential advocates for increasing Israel’s use of traditional diplomacy after Netanyahu had downgraded the influence of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in favor of building personalized relations with prominent global leaders. It will likely be more receptive to playing a greater international role in combating climate change and promoting sustainability than past governments. Lapid has also prioritized a restrengthening of ties with the European Union, as Netanyahu sought to snub the institution and leverage strategic relations with certain EU states to undermine common policies on Israel that he perceived as hostile to the country.

Coalition Cohesion and Political Stability. The government will face challenges of internal cohesion between its disparate group of parties with little in common besides united opposition to Netanyahu. With the slim 62-seat majority—which, to recall, includes one member of the Yamina party who has expressed reservations about the coalition and is not committed to regularly voting in line with it—the government will need all coalition discipline in voting together to both avoid collapse and advance its legislative agenda. Beyond the anti-Netanyahu posture, the main theme holding the coalition together is overcoming the political gridlock of the past two years, which saw four inconclusive elections and the near-complete stalling of legislation. As of its central challenges, the coalition is bound by law to approve the 2021-2022 state budget in the Knesset by early November 2021. A failure to do so could lead to the collapse of the government and the holding of new elections in February 2022.

From the opposition, Netanyahu and his political allies can be expected to leverage any rifts within the coalition to promote its collapse and trigger new elections.

Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery and Public Health. The new government faces challenges from Israel’s economic situation as it tries to position Israel globally as one of the first countries to overcome COVID-19—more than 80% of its adult population vaccinated—and fully reopen its economy. Israel had lifted the last of internal coronavirus restrictions on June 15 amid several weeks of double-digit new cases to let in vaccinated and COVID-19-recovered tourists under a new program beginning in July.

However, cases have surged to several hundred due to the highly contagious Delta variant and the government has postponed opening the country to tourism until at least August. Should the growing number of cases contribute to increased hospitalizations, the government would be pressured to contemplate restrictions on gatherings and movement and possibly further postpone the tourism program. Any reintroduction of lockdowns could trigger societal opposition and harm the economic recovery underway. It too could empower the opposition in its criticism of the government’s handling of the new virus wave and weaken the government’s internal cohesion.

Domestic Strife. The government took power immediately after Israel witnessed its worst internal Jewish-Arab tensions in decades, and amid the backdrop of rising crime within Arab communities. The government’s fragile makeup means that it will need to sensitively address issues related to Jewish-Arab relations and deftly handle any renewed tensions between the communities. Internal violence could bolster pressure from the Arab public for Ra’am to exit the Additionally, Ra’am’s ideological opposition to LGBTQ rights could complicate the commitment of left-wing and centrist parties to advancing LGBTQ-friendly policies by the government.

Separately, the government may face challenges over its policies on the ultra-Orthodox community, a fast-growing minority that currently makes up 12% of Israel’s population. Secularist elements led by Minister of Finance Avigdor Liberman and Minister of Foreign Affairs Yair Lapid advocate for measures to promote greater ultra-Orthodox integration in society through military enlistment and funding for ultra-Orthodox schools conditioned on them teaching secular subjects such as math, science, and English. Any policies toward the community perceived as aggressive and not beneficial to their interests could be met with societal protests by the group and accompanying political pushback from either of the two ultra-Orthodox opposition parties or the right-wing parties in the government—whose bases tend to be more traditional and opposed to coercive measures against the ultra-Orthodox.

Security Escalations. Israel’s border with Hamas-run Gaza remains hostile, with four large-scale conflicts occurring over 12 years and the most recent one—May 2021’s “Operation Guardian of the Walls”—offering no mechanism for long-term de-escalation. Should the new government be challenged with renewed hostilities from the Gaza Strip, it may face pressure internally from Ra’am and left-wing parties to avoid a large-scale military conflict with Hamas. This could be complicated by heavy public pressure for a firm Israeli response and the coalition’s desire to fend off Netanyahu’s narrative of it being a “dangerous, left-wing government.” This scenario could also play out should there be renewed tensions on Israel’s northern borders with the Lebanese militia Hezbollah—especially amid the financial crisis and political turmoil in Lebanon—and/or the Iran-backed Assad government in Syria.

Relations With the United States. Prime Minister Bennett has vowed that there will be “no daylight” between the new government and the Biden administration, though the two sides are likely to face several disputes on key international issues. Chief among Washington’s interest is re-entering the nuclear deal with Iran, as the new government largely shares the same reservations that Netanyahu did about the agreement, seeing Iran as Israel’s primary security threat. The new government may be at odds with the Biden White House on several other issues including growing U.S. concerns about Chinese investments in Israel’s critical infrastructure and emerging technologies, as well as peace talks and the formulation of a two-state solution with the Palestinian Authority. Bennett and Lapid will also face the challenges of trying to restore broad bi-partisan relations with the U.S. Congress in the wake of Netanyahu’s embrace of former U.S. President Donald Trump and overt prioritization of Republicans, at the expense of the Democratic Party. The new government will also face complications from growing anti-Israel sentiment in the Democrats’ progressive wing, which is pressuring President Biden to take a harder line on Israel regarding its Palestinian policies.