Partners, Competitors or Rivals? The EU-China Summit and the Future of the Bilateral Relationship

August 12, 2025

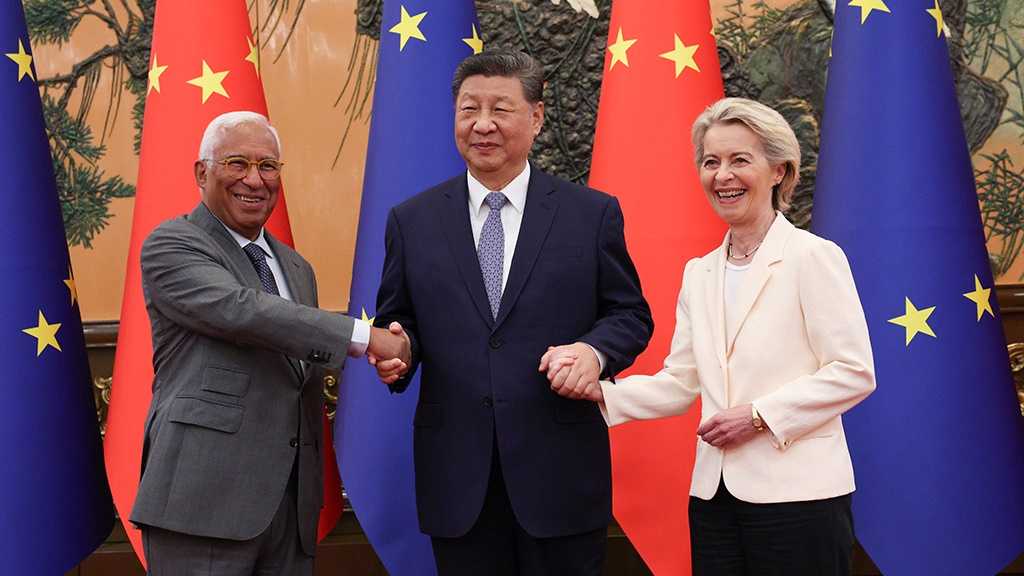

Leaders of the European Union and China met in Beijing in late July for the EU-China Summit. Despite its symbolic significance as the 50th anniversary of bilateral diplomatic relations, there were no surprises and the summit produced few substantive outcomes. The outlook for the EU-China relationship remains uncertain and will be shaped by internal and external factors—not least their respective relationships with the United States.

In 2019, the European Commission described China as “a partner for cooperation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”—encapsulating both the opportunities and the threats associated with this complex relationship. In the intervening six years, EU-China trade relations have changed dramatically. Facing a growing trade deficit, the EU has sought to protect itself from the threat of Chinese overcapacity: the European Commission has issued probes and tariffs on key Chinese exports such as electric vehicles (EVs) and green tech, along with public-tender limitations for Chinese medical devices. Beijing has responded with anti-dumping investigations and threats of tariffs on European food and beverage products. Meanwhile, the fundamental challenge posed by China’s political position on the Russia-Ukraine war presents a seemingly intractable geopolitical issue.

High-level dialogues between EU and Chinese officials earlier this year sought to mitigate the impact of U.S. tariffs. However, tensions rose after China responded to U.S. tariffs by imposing export controls on rare earth minerals. As the EU got hit in the crossfire, Brussels reframed its positioning towards the United States by emphasizing China’s role as a global disruptor. This was particularly evident during the G7 Summit in June, when European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen accused China of “weaponizing” its leading position in producing and refining critical raw materials.

China has reiterated its willingness to build stronger relationships with the EU, especially following President Xi Jinping’s visit to France last year. This positioning partly stems from China’s strategic needs: the European market is crucial for China’s exports, especially given the deterioration in U.S.-China trade relations. And unlike the United States, Europe lacks its own advanced technology so is not deemed a strategic competitor—making it a more attractive partner without “a clash of fundamental interests.”

This willingness has translated into active engagement. Since the start of the Trump administration, China has conducted talks with stakeholders at EU and member-state levels, including Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s trip to Europe in early July and various meetings between Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao and European Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security Maroš Šefčovič. In official Chinese statements, the EU and China are positioned not as rivals but as partners and stabilizing forces in the current turbulent world order.

Although this positive framing has eased tensions to a degree, exemplified by China’s decision to lift sanctions on current and former EU lawmakers, Beijing is not backing down on trade issues. In recent months, the Chinese authorities have announced anti-dumping duties on EU plastics, continued investigations into EU brandy and pork imports and imposed retaliatory measures on EU medical devices. China has also criticized European Commission President von der Leyen’s comments on market access, export controls and overcapacity, calling them unreflective of the current situation. China’s tough stance on trade reflects its continuing economic challenges at home and its perceived need to stabilize exports.

With both sides taking firm stands on the political and economic fronts, the already-shortened summit yielded only a joint statement on climate. The document broadly pledged enhancement of collaborations in energy transition, adaptation, methane control, carbon markets and green and low-carbon technologies.

While the summit disappointed, green development does at least stand out as a promising area for continued collaboration, as mutual investments remain robust and policy alignment persists. Low-carbon advanced manufacturing, in particular, fits within the strategic priorities of both governments. Yet the EU’s focus on de-risking strategic supply chains from China is an obstacle to future collaboration, even in this space. Similarly, the lack of detail on bilateral cooperation in the joint statement may reflect the EU’s sustained concerns over Chinese overcapacity, especially as EV subsidy talks remain stagnant.

EU-China relations will remain fragile, shaped by a range of dynamic factors—of which U.S. relations are the most crucial. Just days after the EU-China Summit, the EU reached an initial framework agreement with Washington, establishing a “reciprocal tariff” of 15%. While the full implications across sectors are yet to unfold, the EU may seek to align with U.S. preferences by attributing trade frictions to China, potentially as a strategic bargaining posture. Although the EU has repeatedly expressed frustration over U.S. unilateralism in global affairs, transatlantic coordination on China-related matters has markedly intensified in recent years. As such, the EU’s future approach to China may be heavily influenced by its evolving U.S. partnership, with Brussels continuing to feel U.S. pressure over its engagements with Beijing.

Similarly, a U.S.-China trade deal would have a significant bearing on China-EU economic ties. U.S. tariff hikes and market access restrictions have not curbed overall trade flows, but rather rerouted them toward other regions, with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Europe surpassing the United States as China’s top trading partners. Although U.S.-China relations show tentative signs of stabilization, such as regular high-level trade talks and U.S. approvals of certain AI chip sales to China, underlying tensions persist. These structural frictions will likely accelerate China’s long-term strategy of trade diversification, including efforts to deepen ties with the EU.

Finally, the stance of individual EU member states is a key factor. The 27 member states have varying attitudes towards China given their trade ties and interests with the country. In this context, the most important variable is the new German government led by Chancellor Friedrich Merz. He has publicly stated his view on the need to de-risk from China, emphasizing that future trade relationships should be anchored in markets perceived as more stable and secure, such as the United States and Latin America. As Germany is seeking to assert its leadership in the EU’s quest for strategic autonomy, its position towards China seems to match that of European Commission President von der Leyen. Meanwhile, Italy, while reiterating the importance of maintaining good relations with China, has also significantly increased alignment with the new U.S. administration. These new factors directly and indirectly give more stability to the European Commission’s stance towards China and are likely to continue to do so in the medium term.

Positive business conditions for multinational companies operating in China will be shaped largely by substantive progress in U.S.-China trade negotiations in the coming months – possibly marked by a presidential visit – and regular high-level visits by EU leaders or high-level trade delegations that ultimately lead to economic agreements. Until then, EU cautiousness and Chinese economic concerns will limit the potential for a meaningful improvement in the bilateral relationship.

Photo: European Council of the European Union