With the recent conclusion of COP29 in Azerbaijan, some commentators felt that the summit failed to make significant enough progress on the energy transition, specifically regarding the mobilization of public and private finance. Perhaps, rather than focusing on the relative cost of action, we should look more closely at the risks of inaction as a way to influence stakeholders to reach agreement on climate finance targets.

The Costs of Inaction

The cost of inaction depends fundamentally on the timeframe being assessed. In developed economies, it can be argued that a short-term mindset is dominant, driven by stimuli such as quarterly earnings updates. However, it is in the longer term that climate inaction really starts to bite and the price of inaction begins to outweigh the price of action. So, what are the longer-term costs of inaction? Below are several that are already influencing behaviours:

1. Increasing Costs of Adaptation

Despite the words “mitigation” and “adaptation” often going hand in hand in climate discourse, there is still a lack of investment in the latter by the public and private sector. This is despite frequent news stories this summer of “unprecedented” weather disrupting social and economic infrastructure. The longer we wait, the higher the costs of adaptation to the changing climate. At the COP29 summit in Azerbaijan, there was a concerted effort to inject adaptation back into the discussion after years of focus on mitigation, but the progress was slow.

2. Tightening Access to Finance

Even though the number of new environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds are trailing in recent years, there is predicted to be $40tn in ESG assets under management (AUM) by 2040. As investors have made it clear that climate risks are important to them, both private and public players will face restricted access to capital if the costs of climate mitigation and adaptation continue to increase.

3. Declining Customer Demand

In today’s market, consumers are increasingly prioritizing sustainability and environmental responsibility. This trend is evident across various sectors, from food and fashion to technology and transportation. Companies that do not adapt may find themselves overtaken by competitors who are more attuned to these demands, leading to a significant decrease in revenues. Ignoring this shift not only alienates a growing segment of eco-conscious consumers but also damages brand reputation, eventually leading to a loss of a licence to operate.

Maximising Value, Minimising Resource Intensity

The argument for incurring costs now instead of later must also take into consideration the impacts of cost to business. It is true that ESG initiatives can come at a cost, and the green premium is real. As French economist Jean Pisani-Ferry recently put it in the Financial Times, with action on climate “you’re basically paying for a resource—a stable climate—you used not to have to pay for”.

It is impossible for an individual business or investor to account for, single-handedly, the cost of inaction. This is where regulation comes in to create a level playing field: prompting action now to avoid the cost of inaction in the future means changing the rules of the game. Regulation by government is likely the only way a framework can be shaped to incentivize companies and investors to take action now. Well-designed regulation incentivises businesses to act now on risks and opportunities that would otherwise cost them significantly more further down the line.

The first examples of this are already in place: the European Union’s Green Deal created the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation (SFDR), and the United Kingdom recently introduced proposals to extend the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to its shores.

But with the lack of significant progress at COP29 and the growing political movement to slow down climate action, it seems unlikely that additional effective regulation will be forthcoming; so, the cost of inaction will continue to grow. For businesses that means developing transition plans that address both mitigation and adaptation, identifying opportunities to become more resilient through their teams and products.

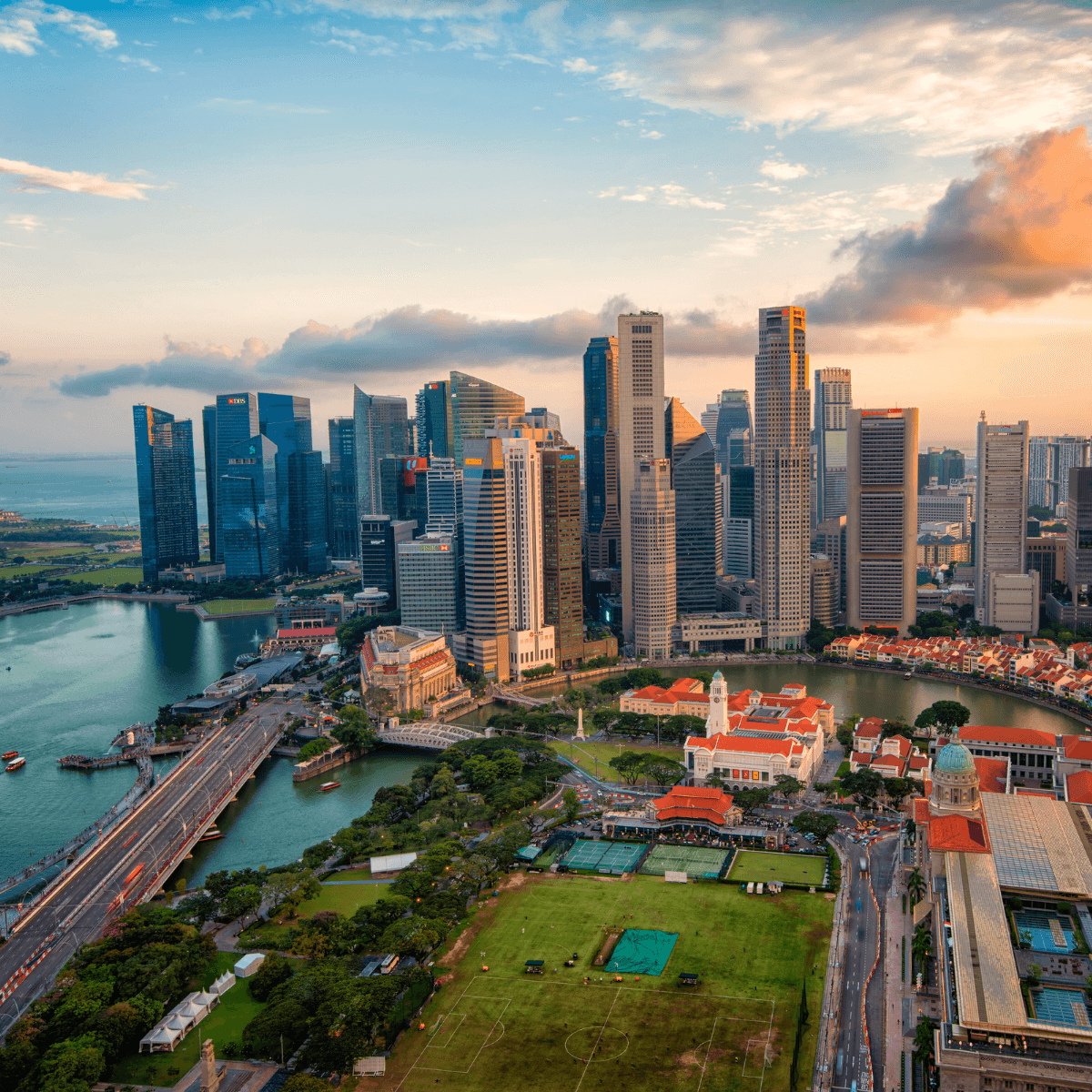

Photo: COP29